Key Takeaways

- AP scoring weights vary, so strategic prep beats equal effort across all topics.

- Knowing how MCQ and FRQ points convert boosts smarter, score-focused studying.

- Understanding scoring rules helps tutors build high-impact, efficient AP prep plans.

Every Advanced Placement (AP) student knows the goal: a 4 or 5 that can turn into college credit or advanced placement. But what most don’t realize is that strong content knowledge alone isn’t enough. Behind that final score is a scoring formula—part math, part strategy—that quietly shapes your outcome.

Each AP exam is weighted differently. Some questions are worth more than others. And your raw performance is not just tallied, but also scaled. Understanding how this works can transform your prep. It lets you stop treating all questions equally and start investing time where it counts. For students, this means smarter study choices. For tutors, it means building plans that prioritize impact over volume.

Before you get into practice tests or cram sessions, take a moment to learn how AP scores are really built. Because in this system, knowing how you are graded is the first step to beating the game. That’s what this article is going to tell you in detail.

The AP score scale: What do 1, 2, 3, 4 & 5 mean?

AP Exams are scored on a 1 to 5 scale. This scale is set by the College Board to help colleges understand how ready a student is for credit or advanced placement. Each score reflects how well the student has mastered the material taught in an introductory college course.

Here’s what each score level means:

- Score 5 (Extremely Well Qualified): Shows the student has mastered the content at the level of an A+ or A in a college class.

- Score 4 (Very Well Qualified): Shows strong understanding, similar to earning an A-, B+, or B.

- Score 3 (Qualified): Shows solid competence, comparable to a B-, C+, or C.

- Score 2 (Possibly Qualified): Shows partial understanding, but usually not enough for credit.

- Score 1 (No Recommendation): Shows little to no mastery of the material.

Setting functional score goals

While a score of 3 is often treated as a passing grade, and many U.S. colleges do offer credit for a 3 or higher, the reality is more strategic for students aiming at competitive schools. Highly selective universities rarely view a 3 as strong enough for placement or credit. Most expect a 4 or 5 before allowing a student to skip an introductory course.

This gap matters for high-achieving applicants. A 3 signals basic competence, but selective colleges want to be sure a student can handle the next-level course from day one. A 4 or 5 shows the depth of understanding needed to succeed without repeating foundational material.

Because of this, students aiming for competitive admissions or maximum credit should treat 4 or 5 as the real target. This shifts both the level of preparation required and the expectations for performance.

The table below highlights the official score definitions and how they play into long-term academic planning:

AP score scale and strategic utility

How the scoring process works: From raw points to final score

The journey from a student's performance on exam day to the final scaled score involves a precise, three-step psychometric conversion process: raw point calculation, composite weighting, and final scaling.

Step 1:

Calculating raw points: The composite score foundation

AP Exams generally consist of two principal sections: Multiple Choice Questions (MCQ) and Free-Response Questions (FRQ), though some subjects include additional components like projects or papers.

The multiple-choice score (Section I)

The MCQ section is scored electronically. The raw score comes only from the number of correct answers. There is no penalty for wrong answers, and leaving a question blank does not earn any points.

This change from the older guessing penalty is a major tactical factor. Since wrong answers do not hurt the score, skipping a question only guarantees lost points. Students should answer every single question. Tutors can train them to eliminate wrong options when possible and then guess on whatever remains. Even a blind guess is better than leaving the item blank, because it keeps the door open for extra raw points at no risk.

The free-response score (Section II)

The FRQ section includes essays, open-ended problems, or short answers. These are scored by trained human readers during the annual AP Reading, held in the first two weeks of June. College professors and experienced AP teachers evaluate each response using detailed, subject-specific rubrics.

In exams like Calculus, each FRQ is usually worth 9 raw points, and students can earn credit not only for the final answer but also for correct steps, reasoning, and conceptual understanding. All FRQ points added together form the student’s Free-Response raw score.

Step 2:

From composite raw score to scaled score

The weighted combination and total raw score

The raw scores from the MCQ and FRQ sections usually have different totals. To make sure each section contributes its intended share to the final score, these raw points are adjusted using subject-specific weights. After the weighting is applied, the two sections are combined to form the composite score. This composite score reflects the student’s overall performance before it is converted into the final 1–5 AP score.

The psychometrics of scaling: Equating and consistency

After the composite score is calculated, it is converted into the final 1–5 score. This step keeps AP results consistent and fair across different test versions and different years.

Two key psychometric processes drive this conversion:

1. Equating:

Not all exam forms are exactly the same in difficulty. Even small changes can affect raw scores. Equating adjusts for these differences so that a 5 on an easier form represents the same level of mastery as a 5 on a harder one. Because of this, the composite score needed for a 5 may shift slightly from year to year, but the standard for earning that 5 stays the same.

2. Evidence-based Standard Setting (EBSS):

The definitions of what counts as a 3, 4, or 5 come from extensive research. College faculty help determine the level of knowledge a student should show to match performance in real introductory college courses. AP Exams are also given to actual college students in related classes to compare results with their course grades. This helps confirm that AP score levels match real college expectations.

These processes reinforce a crucial idea: AP Exams are criterion-referenced. They are not graded on a curve, and the standard does not shift based on how well high school students perform in a given year. The benchmark is fixed at the level needed to succeed in the next college course. Because of this, preparation should aim at meeting a clear, objective performance standard, not just doing better than other test takers.

Subject and exam cariations in scoring

Assuming all AP subjects follow the same scoring system is a major mistake in planning. Each exam uses its own weighting formula based on the skills it measures, so students need subject-specific strategies.

For example, AP Calculus AB gives equal weight to both sections: 50% Multiple Choice and 50% Free Response. But AP English Language and Composition places more emphasis on writing, with 45% from Multiple Choice and 55% from the essay section.

These differences directly shape how students should study. Someone preparing for AP English needs to spend more focused practice on writing, analysis, and argumentation, because those skills make up the majority of the score. A Calculus student, on the other hand, must split effort evenly between problem-solving on the MCQs and showing detailed steps on the FRQs.

Ignoring these subject-specific weights leads to wasted effort and weaker results.

Case study: The Calculus BC AB Subscore

A special scoring feature exists in AP Calculus BC. Instead of one score, students receive two: the overall BC score and the Calculus AB subscore.

The AB subscore comes from the part of the BC exam that covers the same material taught in AP Calculus AB. This section makes up about 60 percent of the test. The subscore is reported on the same 1–5 scale, and the College Board advises colleges to treat it just like a score from the standalone AP Calculus AB exam.

This gives BC students a useful safety net. A student may find the advanced BC topics, such as sequences and series, more difficult and miss a top score on the full BC exam. But if they show strong command of the AB-level content, they can still earn a 4 or 5 on the subscore. That subscore alone can qualify them for credit in Calculus I, even if they do not place out of Calculus II.

Because of this, BC students should prepare for AB-level topics with the same seriousness they give to the advanced material. In practice, they are testing for two separate placement opportunities.

Interpreting your AP score: What it tells you

The AP score report is more than a basic pass or fail. It acts as a diagnostic tool that shows a student’s strengths and weaknesses across different content areas and skills.

The score report as a diagnostic tool

Score reports usually break down performance by section (MCQ vs FRQ) and by the content units listed in the Course and Exam Descriptions (CEDs). For example, a student might score very well in Unit 5 but struggle in Unit 3.

Tutors can use this unit-level detail to pinpoint the real issue. If a student does well on MCQs but performs poorly on FRQs, the problem is not basic knowledge. It is a skill gap in areas like argument building, applying concepts, or synthesizing evidence under time pressure. These are the skills the FRQ rubrics measure.

This kind of insight shifts the study plan. Instead of more broad content review, the student needs targeted skill practice, such as working through DBQs, improving written arguments, or practicing quantitative reasoning tasks.

The impact of single questions

AP Exam scores combine performance across all parts of the test. The Free-Response section often makes up 50 percent or more of the composite score, even though it includes only a few questions.

Since a single FRQ can be worth up to 9 raw points, doing poorly on one item leads to a much larger loss than missing one MCQ. One weak FRQ usually will not destroy an otherwise strong exam, but the point drop can make it very hard to reach the high composite cut-offs needed for a 4 or 5.

Performance data often shows big swings across different FRQ tasks. Many students may score very well on one task but struggle on another. Because of this volatility, tutors need to emphasize steady, reliable performance across all FRQ types. This consistency is what keeps a student on track for the top score bands.

Why scoring insights should shape your AP preparation strategy

The technical details of AP scoring are not abstract academic points, but operational guides for maximizing efficiency and success.

Strategy 1: Precision in point prioritization

It is important to refer to study plans that match the structure of the exam. If the FRQ section makes up 60 percent of the score, then about 60 percent of a student’s focused practice time should go toward mastering those rubrics and performing well under timed conditions. This makes sure the student is investing most of their effort into the parts of the test that matter most for the composite score.

Preparation should also pay close attention to how FRQ rubrics award points. Students need to reliably earn the basic “access points,” such as the thesis point in a history essay or the setup point in a physics problem. These early points often unlock the ability to earn the higher-level points that follow.

Strategy 2: MCQ strategy optimization

Because wrong answers do not reduce the score, students must answer every Multiple Choice question. Prep should include practice in eliminating wrong options, but the final rule is simple: if a student cannot decide, they should guess instead of leaving anything blank. This approach takes full advantage of the zero-penalty system and helps push the raw MCQ score as high as possible.

Strategy 3: Setting the target floor and ceiling (Backward planning)

To score well, students need to set a clear target score, such as a 5, and then use past or estimated conversion charts to figure out the raw score range required, such as earning 80 to 90 percent of the total points. From there, preparation should follow a backward-planning approach.

The study plan should break the goal into small, measurable benchmarks. For example, a student might aim for 90 percent accuracy on MCQ Unit 1 by a set date, or aim to earn 8 out of 9 points on a specific FRQ type by Week 8. These mini targets stack up and help the student reach the overall raw score needed for the final scaled score they want.

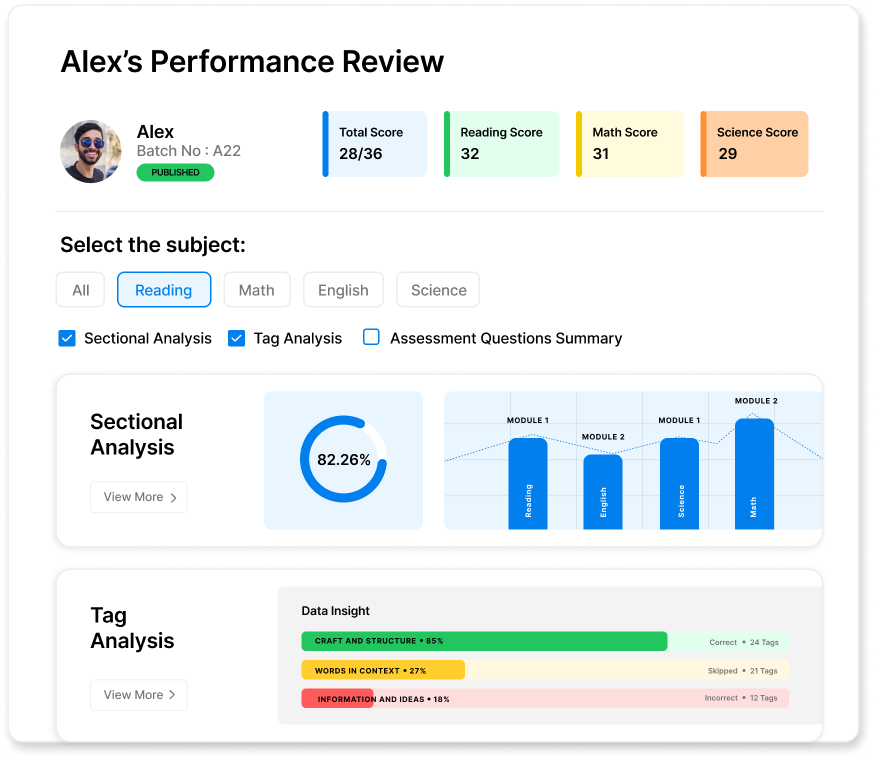

Strategy 4: Utilizing data dashboards for evidence-backed study

Effective learning systems use tracking tools that go deeper than simple test scores. To support focused improvement, study platforms need dashboards that compare a student’s performance to their goals using detailed, segmented data.

Key tracking elements include:

- Scores over time: practice test trends compared with target ranges.

- Section performance: MCQ accuracy versus FRQ point totals.

- Topic or skill mastery: performance broken down by CED units.

Tracking performance this way makes it easy to direct effort where it has the biggest impact. For example, if a student scores 85 percent on MCQs but only 60 percent on FRQs, study time must shift toward FRQ work, even if the student prefers MCQs. The weaker FRQ score, especially when it carries more weight, is the main obstacle to hitting the total raw score needed for their target scaled score.

This data-driven approach keeps effort focused exactly where the most important points are being lost.

Also read: How Many AP Classes Students Should Take?

How EdisonOS helps you and your students decode & improve AP scores

EdisonOS is built to turn complex AP scoring ideas into practical learning strategies for students and clear planning tools for tutors.

Diagnostic precision and customization:

The platform starts with diagnostic assessments that measure a student’s performance across content areas, weighted sections, and specific skills, all aligned with the latest Course and Exam Descriptions (CEDs). Instead of pointing out broad weaknesses, the system identifies a student’s baseline performance in each weighted section of their AP exam.

Personalized roadmap generation:

Using these diagnostic results, EdisonOS mentors create a customized study roadmap. This plan distributes practice time and content coverage according to the exam’s scoring structure. For example, a history student will be guided to spend the right amount of time mastering the FRQ section if it makes up 60 percent of the score.

Advanced tracking and point prioritization:

EdisonOS offers detailed tracking tools and clear dashboards that show progress not just by overall score, but also by section weight and mastery of individual content units. This helps students and tutors target improvement where it matters most. By focusing effort on the highest-value point categories, the platform helps students steadily raise their composite score with maximum efficiency.

Frequently asked questions

MCQs are scored by a computer with points only for correct answers. FRQs are scored by trained readers using rubrics. The two raw scores are weighted by subject, combined into a composite, then converted to the 1–5 scale through Equating, which adjusts for changes in difficulty.

A 3 means Qualified, a 4 means Very Well Qualified, and a 5 means Extremely Well Qualified. A 3 often gets basic credit, but competitive colleges usually give placement only for a 4 or 5.

No. Weighting varies by subject. Calculus AB is 50/50, while exams like AP English place more weight on FRQs. Calculus BC also reports a separate AB subscore.

One bad FRQ can hurt a lot because FRQs make up about half the score and each one is worth many points. It’s not always fatal, but it makes earning a 4 or 5 much harder.

Yes, slightly. Equating adjusts cut-offs based on exam difficulty. But the standard for what counts as a 3, 4, or 5 stays the same across years.

If you want basic credit, aim for at least a 3. If you want advanced placement or are applying to selective colleges, aim for a 4 or 5. Always check the policies of your target schools.

Tutors Edge by EdisonOS

in our newsletter, curated to help tutors stay ahead!

Tutors Edge by EdisonOS

Get Exclusive test insights and updates in our newsletter, curated to help tutors stay ahead!

Recommended Podcasts

.png)

.webp)